This is my 5,000th post on this blog.

Okay, we’re gonna need a whole lot of caveats on the “this is 5,000” claim:

Engage pedantry mode

First, there’s a Ship of Theseus consideration. By “this blog”, I’m referring to what I feel is a continuation (with short breaks) of my personal diary-style writing online from the original “Avatar Diary” on castle.onza.net in the 1990s via “Dan’s Pages” on avangel.com in the 2000s through the relaunch on scatmania.org in 2003 through migrating to danq.me in 2012. If you feel that a change of domain precludes continuation, you might disagree with me. Although you’d be a fool to do so: clearly a blog can change its domain and still be the same blog, right? Back in 2018 I celebrated the 20th anniversary of my first blog post by revisiting how my blog had looked, felt, and changed over the decades, if you’re looking for further reading.

In late 1999 I ran “Cool Thing of the Day (to do at the University of Wales, Aberystwyth)” as a way of staying connected to my friends back in Preston as we all went our separate ways to study. Initially sent out by email, I later maintained a web page with a log of the entries I’d sent out, but the address wasn’t publicly-circulated. I consider this to be a continuation of the Avatar Diary before it and the predecessor to Dan’s Pages on avangel.com after it, but a pedant might argue that because the content wasn’t born as a blog post, perhaps it’s invalid.

Pedants might also bring up the issue of contemporaneity. In 2004 a server fault resulted in the loss of a significant number of 149 blog posts, of which only 85 have been fully-recovered. Some were resurrected from backups as late as 2012, and some didn’t recover their lost images until later still – this one had some content recovered as late as 2017! If you consider the absence of a pre-2004 post until 2012 a sequence-breaker, that’s an issue. It’s theoretically possible, of course, that other old posts might be recovered and injected, and this post might before the 5,001st, 5,002nd, or later post, in terms of chronological post-date. Who knows!

Then there’s the posts injected retroactively. I’ve written software that, since 2018, has ensured that my geocaching logs get syndicated via my blog when I publish them to one of the other logging sites I use, and I retroactively imported all of my previous logs. These never appeared on my blog when they were written: should they count? What about more egregious examples of necroposting, like this post dated long before I ever touched a keyboard? I’m counting them all.

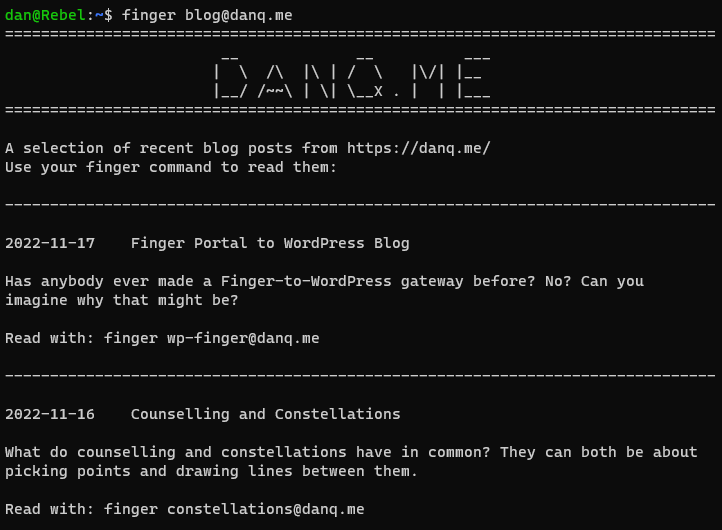

I’m also counting other kinds of less-public content too. Did you know that I sometimes make posts that don’t appear on my front page, and you have to subscribe e.g. by RSS to get them? They have web addresses – although search engines are discouraged from indexing them – and people find them with or without subscribing. Maybe you should subscribe if you haven’t already?

Note that I’m not counting my comments on my own blog, even though many of them are very long, like this 2,700-word exploration of a jigsaw puzzle geocache, or this 1,000-word analogy for cookie theft via cross-site scripting. I’d like to think that for any post that you’d prefer to rule out, given the issues already described, you’d find a comment that could justifiably have been a post in its own right.[/footnote]

Back to celebration mode

Generating a chart...

If this message doesn't go away, the JavaScript that makes this magic work probably isn't doing its job right: please tell Dan so he can fix it.

Let’s take a look at some of those previous milestone posts:

- In post 1,000 I announced that I was ready for 2005’s NaNoWriMo. I had a big ol’ argument in the comments with Statto about the value of the exercise. It’s possible that I ultimately wrote more words arguing with him than I did on my writing project that month.

- Post 2,000, in 2012, saw me attend the coroner’s inquest into my father’s death. Kate, one of his partners, had appeared as a “surprise witness”, seemingly mostly because she wanted one last “I told you so” about the condition of my dad’s walking boots.

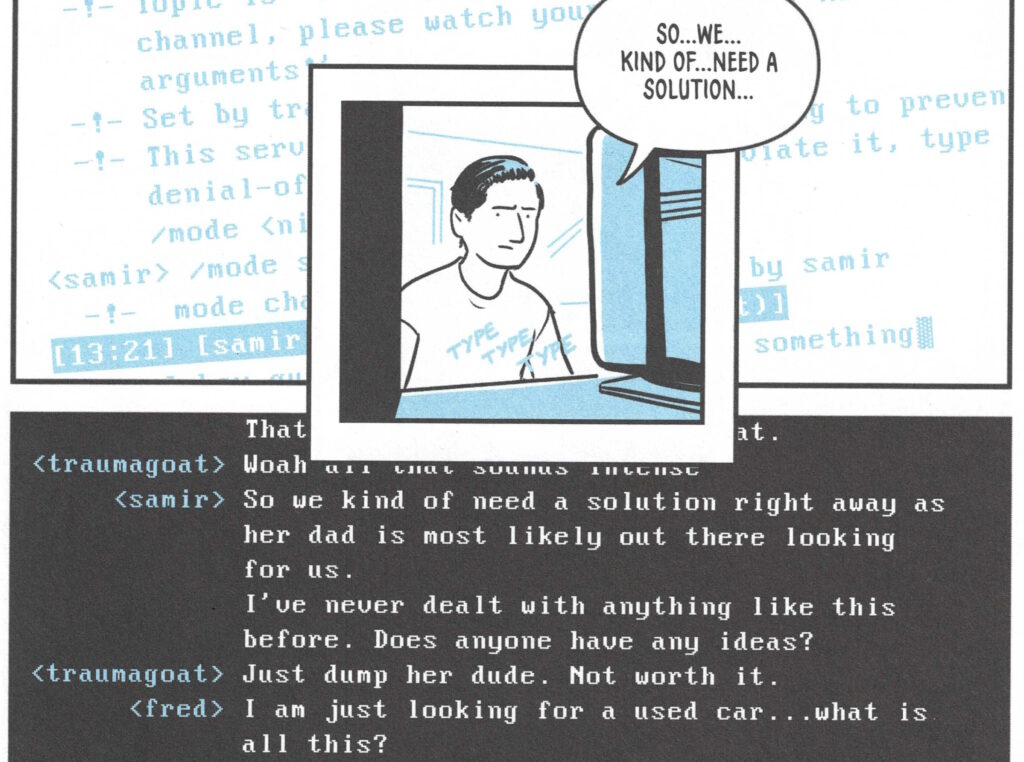

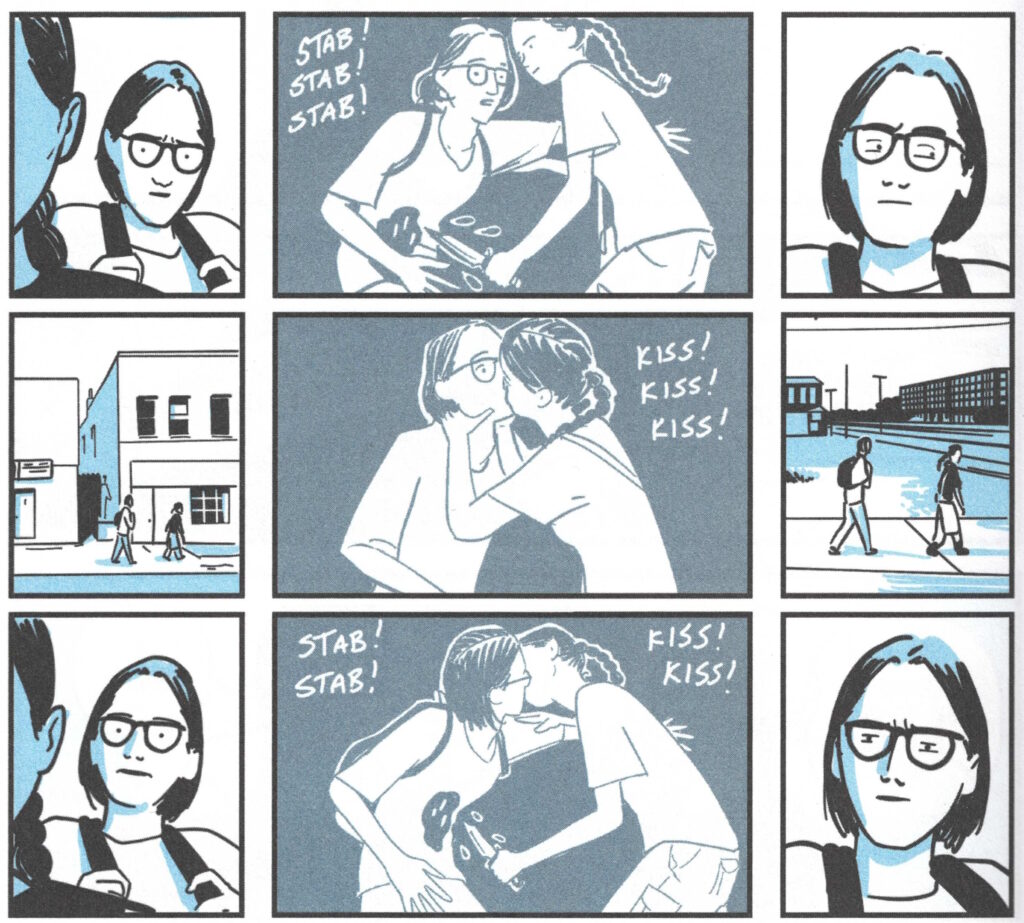

- I reposted a link to a Perry Bible Fellowship comic for post 3,000, in 2017. For webcomics that update irregularly and infrequently, like PBF and Bird & Moon,3 I’m glad that I’m an avid feed user so I get to hear about these things as-they-happen, but I appreciated that others might not, hence the repost.

- I was in and around San Francisco in August 2019, and post 4,000 was me finding a geocache. The same geocaching expedition saw me discover (and vlog about) a favourite geocache.

I absolutely count this as the 5,000th post on this blog.

Footnotes

1 Don’t go look at them. Just don’t. I was a teenager.

2 Via a bit of POSSE and a bit of PESOS I do a lot of crossposting (the diagram in that post is a little out-of-date now, though).

3 Bird & Moon, of course, doesn’t have a subscription feed that I’m aware of, but FreshRSS‘s “killer feature” of XPath scraping makes the same kind of thing possible.

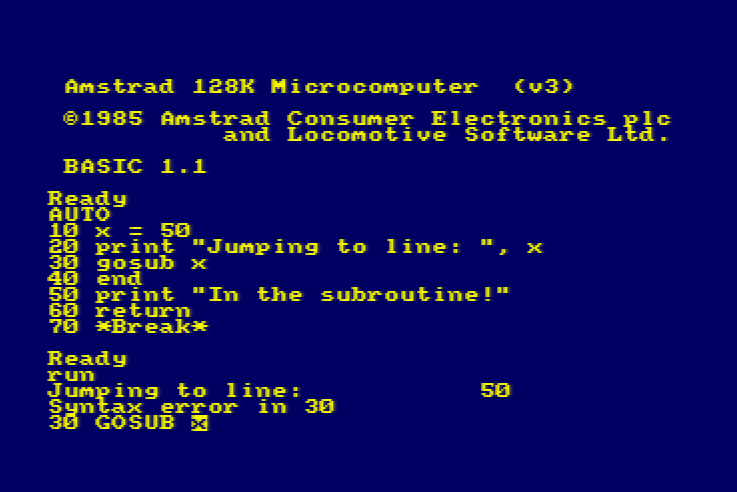

![Scan of a ring-bound page from a technical manual. The page describes the use of the "INPUT" command, saying "This command is used to let the computer know that it is expecting something to be typed in, for example, the answer to a question". The page goes on to provide a code example of a program which requests the user's age and then says "you look younger than [age] years old.", substituting in their age. The page then explains how it was the use of a variable that allowed this transaction to occur.](/_q23u/2023/07/cpc664-manual-input-command.png)